|

May I suggest that you navigate the site via the

index on page 001. PRIOR PAGE / NEXT PAGE PRIOR PAGE / NEXT PAGE

On this page ...

Wearmouth Colliery, an article by Len Charlton,

images of Wearmouth Colliery,

'Wearmouth Gas Coal' a 1913? booklet,

additional material,

page bottom -

re pit

checks or tallies.

Do you want to make a comment? A site guestbook is here. Copyright? Test.

To search for specific text on this page, just press 'CTRL +

F' & then enter your search term. A general site search facility is here.

WEARMOUTH COLLIERY, SUNDERLAND'S VERY OWN COLLIERY

First a few images. Hover your mouse over each thumbnail to read the subject matter.

We thank Len Charlton for the following article

about Wearmouth Colliery.

In the 1800s, the export of coal from Sunderland staiths was a major

industry. Much of the coal was being transported from collieries south and west

of the town itself, but the largest of all of the Durham collieries was actually

a deep mine in the very heart of Sunderland. It was originally called Pemberton

Colliery, after the Pemberton family whose records went back to AD1400 and who

had become very wealthy landowners in the Durham area owning land at Monkwearmouth used for glass works. By the early 1800s, they had started to

speculate in coal mines in the Wigan and LLannelli areas, and so in 1822, when the 'Hetton Coal Company, Limited' found a rich deep coal seam, they decided to invest in a new mine

on their Monkwearmouth land with a view to exploiting these deep seams.

Sinking the shaft (A) commenced in 1826 but they ran into serious

problems. Close to the river and 1 1/2 miles from the sea, the top of the shaft was

only 87 ft. above high water and at 344 ft. they were pumping 3,000 gallons a minute

out of the shaft and an iron lining had to be fitted. At 1,000 ft. they struck more

water and were advised that the whole project was hopeless. There were three

Pemberton brothers involved, Thomas, Richard and Ralph and having spent over 6

years looking for a rich deep seam they might well have given up but instead

pressed on saying "... we'll go on till we sink down to hell, and then, if we don't get coal,

we'll get cinders!". Their confidence was proved in 1833 when they reached a 2

ft.

6 in. seam and then in 1834, at 1,578 ft., they found the 5 ft. 8 in. thick 'Bensham' seam.

By now the colliery had built riverside staiths to which coal was

transferred directly from the pit mouths in wagons running on inclined gravity

planes. The Wearmouth staiths were right opposite the Hetton Staiths on the

other side of the river.

The most interesting image that follows shows probably just a part of the Wearmouth Colliery staiths at riverside. Those staiths were, of course, on the north bank of the

River Wear. The photo was taken from the

south bank with the Hetton & Lambton Staiths, at left & right respectively, in the foreground.

The image below would seem to have originated at the 'www.englandspastforeveryone.org.uk' site,

whom we thank. A print of the image was sold on eBay on Apl. 30, 2012,

with this listing image,

a much more detailed image, in fact, but smaller, of course.

Production increased rapidly, and in 1836 51 ships

loaded 13,707 tons of 'Bensham' seam coal for London.

A year later, 61 ships loaded

16,768 tons, and in 1842 the total production reached 20,854 chaldrons. Now

convinced that richer deposits lay deeper, a new shaft (B) was started in 1841.

Once again with there were many problems. Apart from water the depth of the pits

generated heat which on occasion was well into the 80 degree range, which caused serious skin problems

for the miners. But work continued and in 1843 (A) shaft reached

the 'Hutton' seam 4 ft. 8 in. thick at 1,720 ft. By 1850, both (A) and (B) shafts were

working this rich seam.

In 1847, Ralph Pemberton, the only surviving brother died and the Pembertons sold their shares to Wm Bell and Partners who became the new owners.

The colliery lost its Pemberton name and became known as 'The Wearmouth

Colliery'. The

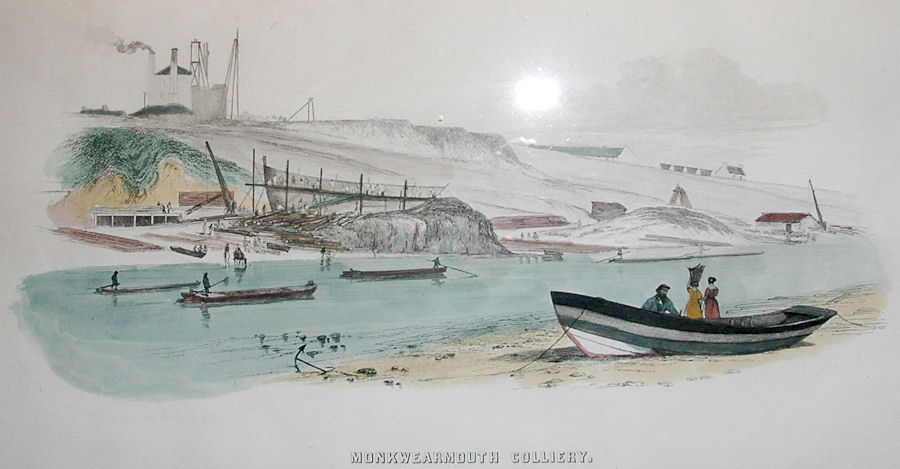

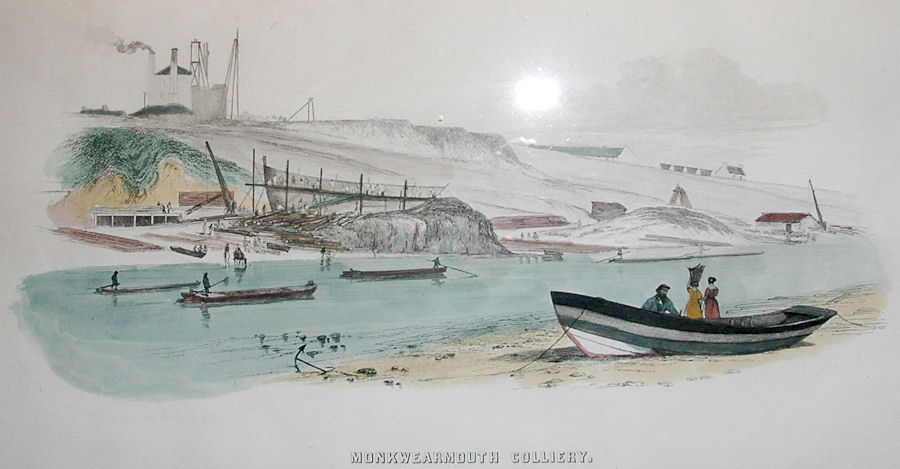

image that follows dates, I understand, from 1860 & may have been a page from an

early book. Showing the pithead at top left & coal wagons rolling downhill

to the water's edge. And also shipbuilding in progress, with a ship being built & whole tree

trunks being worked to provide the necessary timbers. The image can be seen, in

a larger version, here.

An 1844 work by T. H. Hair, I am advised. I learn from eBay university that the print appeared in

W. Fordyce’s ‘A History of Coal, Coke, Coal Fields and the

Manufacture of Iron in the North of England including

Estimates of the Capital Required to Embark in the Coal, Coke or Iron Trades etc', (& that may not be the full title!) sometimes called just

‘Coal & Iron’. Published by

Sampson Low of Ludgate Hill in London in 1860.

For some 40 years, the colliery had moved its coal by road or (mainly)

through the staiths.

|

In 1876 the Hylton, Southwick & Monkwearmouth railway

line was opened. This mineral railway branched off the Stanhope-Tyne railway to

follow the N. bank of the Wear round the colliery & join the main North Eastern Railway line

through Sunderland. It became an important additional outlet for the

colliery.

Webmaster's comment. At left is an image of the railway line that served Wearmouth Colliery, in an image taken from the west. River Wear is at right. The cylindrical structures clearly

visible at the

right of the image are storage facilities

for the riverbank staiths, and the tall 'D Shaft' head box towers up right behind them. |

Many collieries worked under the sea but Wearmouth Colliery was breaking

all records both for working depths & for undersea distances.

|

In 1893 the 'Maudlin'

& 'Hutton' seams were being worked at 1,590 & 1,722 feet

with some faces over 2 miles out to sea (3 1/2 miles from the shafts). As the

seams were flat, roadways could be built & interconnected easily forming huge

underground warrens with long straight roadways constantly moving miners &

coal between shafts & faces by both engine & gravity rope planes. It was

said that 'more than 20 miles of steel-wire rope were in daily use in the pits

and in one of the longest engine planes where the empty train is taken in at the

same time that the loaded one is brought out, there are 126 tubs on the road at

one time.' |  |

Webmaster's comment. At

right above is an image of Wearmouth Colliery, as

depicted in a R. Kane watercolour, painted in 1879. Said to be as viewed from

the south-west but I think from the west may be more accurate. Ex an eBay item in

late Sep. 2011 - a 'Beamish' postcard of the painting.

The card does not indicate the direction of view.

With the colliery now thriving, the new owners decided in 1906 to sink a

new shaft (C). Many problems had arisen when sinking the earlier shafts owing to the

water content of the ground and when C shaft was started a ground freezing

process was used. By first boring holes round the shaft position, pipes were

inserted through which brine was pumped to create a cylinder of frozen earth.

During this lengthy process, foundations for the winding engine and scaffold

winch were constructed around the works and then the shaft itself was sunk

through the frozen earth and the cast iron shaft lining positioned. C shaft was

opened in 1910, and with three pit shafts now working, the colliery was by 1914

employing 2,600 people of whom 2,200 worked underground. After WW1 this number

dropped to 1,300 but after Nationalisation in 1947 the picture changed

dramatically.

On Jan. 1, 1947, the National Coal Board (in 1987 renamed

British Coal Corporation) took over the mine, upon the nationalisation of the

U.K. coal industry.

When it took control, in 1947, the National Coal Board had a colliery over 120 years old but with massive reserves

of coal left, largely undersea. It was decided to exploit these with a

complete reconstruction of the colliery at a cost of some £6 million (in the

event additional projects brought the total to c. £10 million) The seams to be

worked were the 'Hutton' seam and the 'Maudlin' seam which was estimated to reach 12

ft. thickness. It was a 22 year project designed to modernise automate and extend

the entire workings, above and below ground and move into the new age of mining.

The plans included:-

1954-1967 Sinking a new shaft (D) to 2,140 ft. with a 2,000 hp winder

Deepening Shafts (A) & (C) to 1,850 ft.

Underground : New roadways, locomotives, rails, conveyors and coal face

equipment

On Surface New ventilation, coal processing and drying plant, baths,

canteen

1966-1969 Building riverside coal and stone bunkers plus new

conveyors to existing and new staiths

After 1967 Ongoing roadway and conveyor extensions and new surface

plant as required

Work started in 1954 some distance South West of the old shafts. A level

terrace was excavated 80 ft. deep. to accommodate the various buildings and

plant, provide a drilling platform and equipment for D shaft to be started.

Some 70,000 cu. ft. of dirt had to be removed just for this. The existing shafts

A & C were deepened to 1,850 ft. and D shaft was then sunk to 2,140 ft. using an

improved freezing system similar to that used in 1906. New winding engines were

installed in modern pit head tower-like structures.

Many miles of conveyors and rope hauled wagons had to be removed from

the old roadways. There were four individual railways running 850, 1,450, 2,150,

and 1,200 yards hauled by 100 hp electric motors to be dismantled. The roadways

themselves had to be enlarged and extended to handle the new diesel locomotives

which were designed to run at 8 mph. At the shaft bottoms complete railway

stations with platforms and tracks were excavated. On the surface, the entire

layout round the pitheads was changed. The processing and bunkers were now a

tight cluster of 8 tall cylindrical bunkers on the riverside built further up

river than the old staiths. They stored the different grades of coal and fed

long conveyors which ran both south along the river to drops at Wreath Quay and

north to drops to the Monkwearmouth railway. Stone and rubble could be dropped

from the bunker bases into barges to be taken for dumping in deep water. To

check the undersea seams as the workings extended outwards, 5 floating rigs

carrying boring towers and equipment were in constant use. These rigs worked up

to 4 miles out to sea and measured sea depth, overlay type and seam depth and

thickness.

The rebuild ended in 1976 at which time there were approximately 2,300

men employed at the colliery of which 28% were employed at the coal face, 57%

were elsewhere underground and 15% were at the surface. During the rebuild, the colliery had

continued in full operation and the amount of organisation and planning required to

fit everything together must have been mind-blowing. It was seen as a complete

transition into the future with mining automation replacing the worst of the

dirt and sweat of the old days, with changes as noticeable on the surface as

underground. The sheer size of the workings by the 1980s was vast. They

extended (at more than one level) from the shafts 4 or more miles to the East

and in the other directions eventually reaching within half a mile of the

workings from Silksworth Colliery (4 miles away).

|

Records show two major accidents in the colliery's life.

In 1862, 5 were

killed when a shaft cradle gave way, and in 1869 7 died in an explosion. There

were many individual accidents and deaths usually from wagons or rock falls,

accepted as part of mining life. But Monkwearmouth suffered no major disaster -

in an industry where a single tragedy would often take many lives and a major

explosion or pit collapse could devastate a community. There were very few pits

indeed which could class 7 deaths as the most serious accident to happen in over

150 years. | |

|

The colliery (depicted above in 1956) closed in 1993 only 17 years after the £10 million rebuild. Although arguments over the pit closures still continue, the site has

become a source of great pleasure to all Northern football lovers. In October

1994, the old winding towers were finally demolished and the following year

Sunderland Football Club put forward a plan to build a stadium with 34,000 seats

on the site. The existing ground at Roker Park had largely standing terraces and

was far too small for such a building. The necessary permissions were granted. During building,

the capacity was increased to 49,000 and even allows further expansion to 63,000.

The stadium had been known colloquially as the 'Wearside Stadium' and 'New Roker

Park', but the new stadium was eventually called 'The Stadium of Light' - referring to the famed

miners' lamp and marked by a Davy lamp monument at the stadium entrance. The East Stand

has the Sunderland emblem on the seats, while the North Stand has the slogan

"Ha'way The Lads". The stadium was opened on July 30, 1997 by Prince Andrew, the

Duke of York.

On both sides of the river, the old staiths and railways have

all gone, replaced by public parks.

Gone indeed! Witness the following dramatic series of images of the 1994 demolition of the D shaft head box tower.

For a long time, I wondered what had been done with the deep mine shafts. And

now, thanks to Steve Duffy of Sunderland, we know the answer. Steve advises me

that the bottom of the shafts were sealed off at around

20-30 feet in each direction with timber frame & rubble then concrete was

poured down the shaft. While at the surface the shaft was capped about 30-40

feet down with a steel plate & then the rest was filled in with concrete.

Thank you, Steve, for that interesting information!

Few now recall that both banks of

the Wear upstream from the bridges were once areas of toil and sweat rather than

enjoyment and pleasure.

Len Charlton

Abingdon, Oxfordshire

Jan. 30, 2009

Note:- The 'Durham Mining Museum' has extensive data available about Wearmouth Colliery.

Their page is available here.

IMAGES OF WEARMOUTH COLLIERY

Just one image so far.

The fine image of Wearmouth Colliery that next follows is from a

postcard mailed back in 1905. An eBay item that closed on Oct. 31, 2012.

The image appears here thanks to

the kindness of eBay vendor 'rascotsman', of New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada.

Do drop by his eBay store, which can be seen

here!

A much larger version of the image can be viewed here.

The image would seem to be available also in colour, as you can see by

this expired eBay item.

And a copy of the card is e-Bay available in Mar. 2015.

The site is now,

of course, occupied by Sunderland's new 49,000 seat football stadium - the 'Stadium of Light'

- opened on Jul. 30, 1997 by Prince Andrew, Duke of York.

A 'WEARMOUTH GAS COAL' BOOKLET

|

I am

happy to be able to next present material from a modest booklet, entitled 'Wearmouth Gas

Coal', published by 'The Wearmouth Coal Co. Ltd.', the then owners of the Wearmouth

Colliery.

The booklet is of 16 interior pages, 5 pages of which are black & white photographs, & a very

large map of the coalfields.

The booklet does not bear a date of publication.

not even on the map. Help, re dating, is offered however, by the first image below which

shows a vessel only built in 1913. And other data in the booklet may help

also, (available below) but have not helped me so far. Five of the full page photographs are of particular interest

&

follow:- |

The first image shows a 'Loaded Steamer alongside Wearmouth Staiths,

Sunderland'. Now you surely will be unable to read the name of the vessel. But,

with the aid of a magnifying glass, the name of the ship can be

read on the original image. It is of Caterina Gerolimich, 5515 tons, built at San

Rocco, near Genoa, Italy, in 1913. The booklet states that there were three staiths at the

colliery site.

Two visually interesting images of Wearmouth Colliery.

Of self explanatory content.

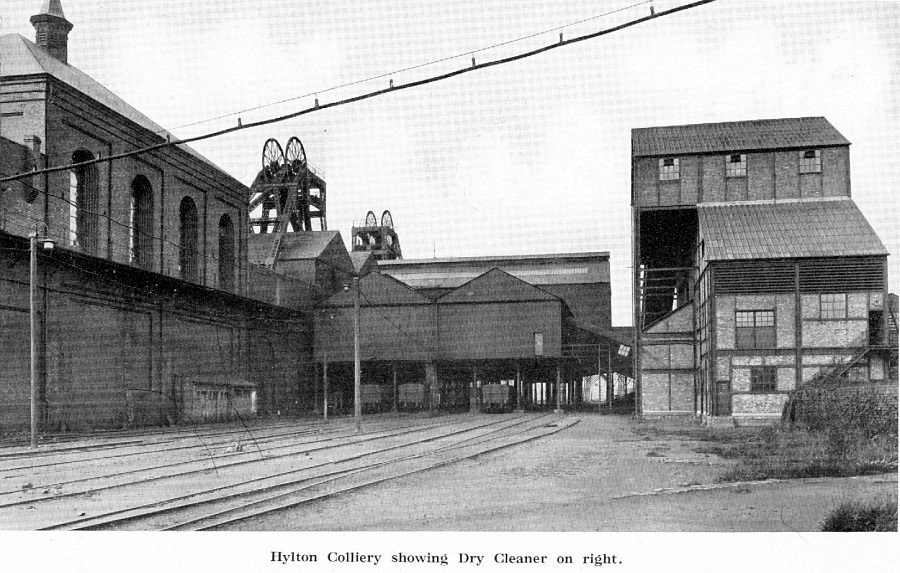

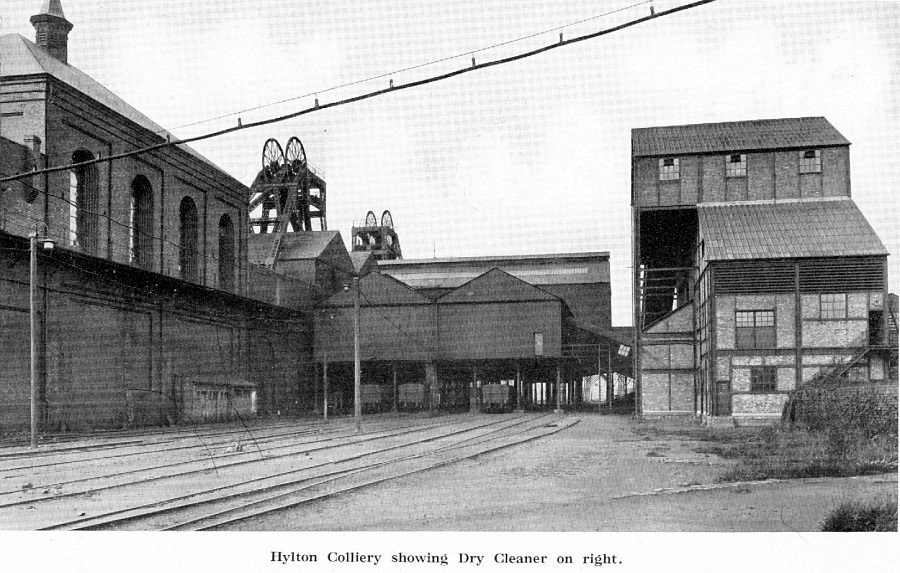

And two fine images of Hylton Colliery, also owned it would

seem, by 'The Wearmouth Coal Co. Ltd.'

The rest of the booklet.

Other than the 5 images shown above and the map.

The map? Which is large & full of detail. Scanning of the map would be most difficult.

It is about 16 x 19 inches in size & could only be scanned with my scanner in

multi sections,

the sections then needing to be stitched together into a complete image. Not

easy to do successfully. I have often wondered how commercial businesses are

able to scan very large items. But I have never

learned exactly how they accomplish the task. Do you happen to know how they do it?

I hope, however, to soon scan

for this page the portion of the map which shows the territory of 'Wearmouth Coal Co. Ltd.'.

Which territory extends from way beyond Hylton Colliery in the west to far out under the North Sea

in the east. Indeed here it is. The mine territory would seem to have extended

to three miles out from the North Sea coast. Len Charlton comments that seeing the map, it

was probably true that coal miners working deep in the Silksworth Mine could

hear mining activities going on in the adjacent Wearmouth Mine.

Followed by the map title section.

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

1) A

'mariopteris nervosa' fossil from Wearmouth Colliery. An eBay item. Such a fern

was, I read, common in the Carboniferous period, between 300 million & 270

million years ago.

2) I learn that John Elliott McCutcheon wrote 'A Wearside Mining Story',

(its cover), an account of the sinking of Wearmouth

Pit, & the birth of the Durham Miners' Association at that

colliery. Published privately by 'McCutcheon' in 1960. He also wrote at least

two other books related to Durham coal mining - 'The Hartley Colliery Disaster'

of 1862 (its cover), a

volume which he privately published in 1963 (& was reprinted in 1974 by David R. Little of Schwarz Holywell) & 'Troubled Seams', published in 1955 by J. Greenwood & Sons,

also about the Seaham pit, I do believe. And republished in 1994 by County

Durham Books.

He was for many years, I understand, the Seaham librarian. Alison Dixon is, I

read, his great niece.

I wonder where John E. McCutcheon was buried? And his dates of birth & death.

His older brother was born at Seaham in 1890. In a letter addressed to Mrs. J. E. McCutcheon dated Oct. 16,

1974, contained within the 1974 reprint of 'The Hartley Colliery Disaster',

David R. Little refers to Mrs. McCutcheon's late husband. No specific

date of death was stated re the author.

3) The Carp Ponds

Lloyd Stridiron, in or about 1954, was with the Safety Staff at Wearmouth

Colliery - Lloyd is at right in one of the above images he has kindly provided, speaking with L. George Holt

of Ventilation.

Anyway, Lloyd has been in touch to mention that at that time there were three very large ponds

on the site (located near the cooling tower shown above) - ponds which were unique in all of England. The steam boilers that provided the power for the winding houses

produced as a by-product a lot of warm water & that water was fed into these

three ponds. Which were stocked with a species of golden carp that turned a sort of blue black as they grew bigger

& older in the warm water. The warm waters also encouraged the growth of water

plants, including some plants

imported specially from Italy, to both aerate the water & feed the fish. Wearmouth was,

Lloyd advises, the only place where those particular plants grew, plants which

were in great demand by British aquarium lovers. Every two years, the aquatic

weeds were apparently thinned out by a firm who then

sold then for aquarium lovers across the country to buy.

The system came to a

most unfortunate end, alas. 'Some clown made a connection to the wrong pipes and fed some of the water from the freezing re-circulating system for the new 'D' pit sinking'

into the pond system & ended up killing both the fish & the vegetation.

4) Wm. Green, Undertaker - The webmaster has

included the following item only after a lot of thought - as to whether its

content might offend even a single site visitor.

While I think that it may very

well so offend, I have, none-the-less, decided that the 1911 image merits

inclusion even though the subject matter is sad. Low on the page, where less

prominent, at least. Perhaps an appropriate

subject, however, on this particular page since loss of life or injury in a mining disaster was

never far from a miner's mind.

An eBay item in Jun. 2012,

offered by major eBay vendor 'atlantic-fox'.

Do drop by his store - you may well find an old document that especially interests you.

May I suggest that you navigate the site via the

index on page 001. PRIOR PAGE / NEXT PAGE PRIOR PAGE / NEXT PAGE

TO END THE PAGE

For your pleasure & interest.

Within the text above, I showed an image of a 'pit check' or 'tally' from Wearmouth Colliery. While I think that the image is visually interesting, it is just one example of thousands of such items from the many U.K. collieries. I state

U.K., not because I am

sure that such pit checks/tallies were only used in the U.K. But that said, a recent search on eBay produced no such items in use in other coal mining areas of the world.

What were they used for? This site tells us essentially that 'when a miner went to work at a pit, he was issued with a lamp check or a pay

check.... The number on the check or tally was personal

to each miner & prior to going down the pit the miner would exchange his tally

for his numbered lamp from the lamp room. When the lamp was returned at the end

of the shift, the tally would be returned to the miner. In the mid 1900s, the practices were changed. Prior to going down the pit, the miner would give one

of his tallies to the 'banksman' at the pit head - and would retain another one

with him for the duration of the shift. When returning to the surface, the miner

would give his personal tally to the banksman who would in turn pass it on to

the time office or to the lamp room. Some mines had different systems. Using this

system, it was possible for mine management to keep track of who was where

in the complex & for what periods. Tallies were produced in a great variety of shapes, sizes & designs.

Although usually made of brass or zinc they can also be found in steel or

aluminum - & recently magnetic strip 'swipe cards' have been used.'

I presume that somewhere it may yet be known which specific miner at Wearmouth Colliery was issued pit check # 905. And #

1359 below.

Alan Kirtley has advised, (thanks!) that he spent 4 years

down Wearmouth, mostly on the Busty level, 1850 ft. down & out under the North

Sea. His issued tag (or rub) was #293, & he and others had, in fact, two tags of identical number. One, of zinc,

was handed in to the 'banksman' on the way down. The other tag, made of brass,

was handed in as you came out. The brass tag, in a perfect world, would have

been given into to the 'banksman' when exiting the pit, but with 150 men

simultaneously exiting, that was not very practical. So in reality the brass tag

was dropped into a bucket! Alan adds that the tags were of metal, since, should

there be a fire, they would not burn & would be used to identify a miner. What a

jolly thought!

Alan Kirtley has further advised:-

Seaham or as it was known,

'THE KNACK', in its latter days was used as a

training pit. I did a month training there before going on to Wearmouth. The first part of

the training was in the class room learning the basics of mining, first aid

etc., then down the pit. My first time down, we went along some very low roadways

& all of a sudden we came to what I would call a cavern. It must have been 20

to 30 foot high & as wide - all over the walls miners from the past had chalked

names & dates - it was amazing to read comments left by people 50 year before I

was even born.

At Wearmouth the cage at C pit had 3 decks that held 50 men each. I am not

sure how many would be in a deck as it was a race to get to the bottom deck &

everybody just crammed in. The bottom deck was the best as when it got to the

surface this was at ground level & gave you an advantage to get to the showers

first - while the miners from the mid & top decks had to come down stairs. The revenge of the

upper decks was to empty their water bottles on the way up the shaft to the

discomfort of the men on the lower deck. At the end of the 4 main shifts known

as First, Back, Nights and Tub. The cage would make 3 trips full of men

to the surface & there was always a cage for the stragglers that held 27 men.

Lloyd Stridiron who served in the Safety Department at Wearmouth

Colliery, advises re tokens or tallies ... I had the job of helping with the ID

tokens or tallies at Wearmouth Colliery around 1954 & was issued token No. 187.

Token No. 1162 was my father's, & I still have it today. The two tokens in your article

would have had a

number of owners, since they are pretty well polished with use.

I don't know who had my

token before it was issued to me, or who owned it later on, but for about 2 years it was mine as I worked on the Safety Staff of Wearmouth

Colliery. There were three tokens issued to each worker:- a) brass, retained by the

underground worker whilst in the pit, but not by shaft bottom workers, who were

not issued disks. b) lead for descending personnel & c) silver for each miner's

safety lamp. The brass & the silver being returned to the Token Cabin at the end of

a shift to evidence the worker had physically left the pit.

There was another 'tally' which was used for hewers & fillers of tubs in/on a different work area which was placed on the tubs of coal for weighing purposes

& issued from a different tally cabin above the screen picking belts area.

Thank

you, Lloyd, for your interesting words!

What next follows is a composite image

of such items from across U.K., which shows some of their many shapes & sizes.

Just a sampling of the many hundreds if not thousands which are available. I do hope you enjoy it. Comments?

A Hylton Colliery pit token.

Thomas M. M. Hemy Data Pages

01,

02 and

03 are now on site. Plus all

of the other image pages, accessible though the 'Hemy' index on page

05.

To MV Danmark Slider Puzzle

page &

to the

Special Pages Index.

| A SITE SEARCH FACILITY

THE GUEST BOOK - GO

HERE

|

|

|